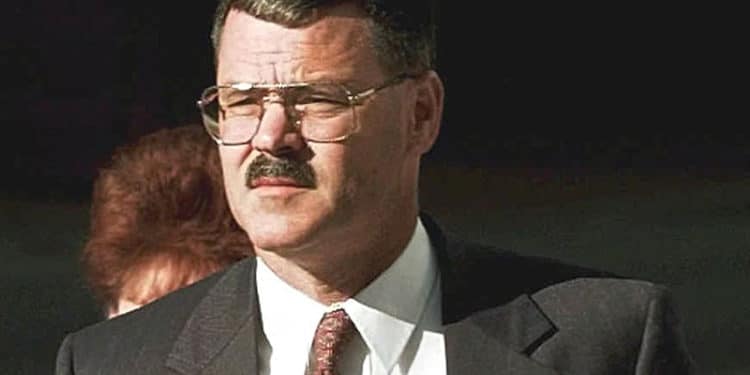

Frederic Whitehurst is a warrior. He fought in Vietnam, and he fought the United States government, establishing himself as the first person to engage the whistleblower system at the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI). He has mentored and provided support for whistleblowers across the world. Whitehurst is tall, highly educated, and takes command of a room. He was an accomplished FBI Special Agent who represented the FBI’s best. Then, like lightning flashing across a darkened sky, he was gone. After twelve years of dedicated service, he was forced out because he blew the whistle on malfeasance, misconduct, and poor lab practices in the FBI Crime Laboratory.

Whitehurst was born in Newport, Rhode Island. He grew up with a father who was a naval officer and often at sea. Whitehurst had an older brother and twin younger brothers. “I liked to work,” said Whitehurst. “We mowed 35 lawns a week.” Whitehurst’s father bought him an 8-foot sailboat when he was eleven. Whitehurst was told not to leave the cove with the sailboat, but he loved to be adventuresome and promptly left the cove to venture into the river, which led him into the Chesapeake Bay and the shipping lanes. These adventures usually ended with Whitehurst calling his mother to pick him and his brothers up in a place far beyond the cove. At an early age, Whitehurst seemed to be fearless, and this trait has been with him to this day.

Whitehurst advised that his core strength probably came from his mother. She had a solid work ethic and a powerful moral code. His mother had the strength of a Southern woman, but the “old white male empire had beaten her down.” Whitehurst said his mother fought and beat the system every time she could. “She was curiously opposed to the fact that because she was a woman, she was not allowed,” he said. She would tell Whitehurst that “some people think that because you are not stepping on them, that they can step on you. Nobody steps on me.”

His father’s job in the Navy allowed Whitehurst to travel worldwide, and he spent his last year in high school in Korea. Whitehurst had great respect for his father, who was incredibly patriotic and an uncommonly hard worker. Whitehurst’s desire to work was established at an early age, and he concentrated on working; he did not a party or date girls, instead preferring to restore boats and equipment. He did not “have a lot in common with the kids” around him in the ’60s and refers to himself as a “conservative Republican” who just wanted to work. In his senior year of high school, Whitehurst joined the Navy Reserve and went to boot camp after graduating high school. He was honorably discharged a few months later because the Navy found he “was a sleepwalker,” which might prove deadly on a Navy ship.

During his couple of months in the Navy, Whitehurst received the Navy-Marine Corps Medal for heroism at seventeen years old. On January 15, 1965, his first day in the Navy, Whitehurst rescued individuals from an icy lake who had accidentally entered the lake by car during a storm. Whitehurst, who immediately jumped into the freezing water in his pea coat and naval shoes, almost drowned. Whitehurst received the title of “hero” at an early age.

In 1965, Whitehurst attended East Carolina University and lived with his grandfather. Although not a remarkable student in high school, Whitehurst found his calling in Chemistry. He spent his college years in the library, eschewed any social functions, and commanded top grades. In his senior year, suffering from burnout pursuing a triple major, Whitehurst took a bus to New York City and joined the United States Army on September 30, 1968.

Whitehurst was sent to Fort Jackson for basic training and volunteered for Vietnam, joining the Tiger Brigades. He spent three years in Vietnam. While there, Whitehurst blew the whistle on war crimes. A thirteen-year-old Vietnamese boy with a grenade was discovered by a military group that included Whitehurst. They tortured the boy, cutting off his ears and nose and breaking all of his limbs. Whitehurst walked away and declared he wanted to leave. He entered a chopper, demanding that they take him away from the scene, which they did. Whitehurst displayed the core of his moral compass, which would not allow him to participate in or sanction torture. He said his superiors were reluctant to return him to his unit, fearing that Whitehurst would suffer at the hands of fellow military members for telling the truth to power. Whitehurst was sent to an Intelligence unit where he interrogated prisoners of war for two and a half years. Whitehouse turned down a Purple Heart after losing friends in a firefight but received four bronze stars, an army commendation medal, and a campaign medal.

In April of 1972, Whitehurst returned to the United States, traveled to western Virginia, “got in a canoe and paddled 1800 hundred miles to New Orleans.” He lost a tremendous amount of weight and was placed in a VA hospital where they found he had hookworms. This was a difficult time for Whitehurst, as he displayed a temper and suffered from depression after serving in Vietnam.

In the fall of 1972, Whitehurst went back to college in North Carolina. He married his childhood sweetheart Cheryl in 1973. Duke University recruited Whitehurst for its Chemistry Ph.D. program. After five and a half years, then 32, Whitehurst got his Ph.D. Next, he proceeded to Texas A&M, where he received a Postdoctoral Fellowship. After six weeks and realizing “that he would never be an academician,” Whitehurst applied to work at the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) and the FBI.

The FBI accepted Whitehurst. His first office was located in Houston, and he was placed on the reactive crime squad. Whitehurst then served in Chico, California, for eighteen months. Whitehurst was known as a hard worker and possessed a unique talent, as he was able to pierce through a suspects’ facade. He was able to “deal with [suspects] from an honest and true base.”

Whitehurst was transferred to Los Angeles in 1984 and worked narcotics, establishing an admirable bank of informants. He worked hard and was noted as “overenthusiastic.” In June of 1986, Whitehurst was transferred to the FBI crime laboratory as a Special Agent and quickly climbed the ranks to Supervisory Special Agent. No one in the lab had the background that Whitehurst possessed. His coworkers’ experiences were not from a scientific background; Whitehurst stated that “they established data that supported guilt, rather than question alternative explanations for the data.”

Whitehurst found the lab equipment to be old, rusty, and dirty. He started cleaning the lab, beginning at 6 am and staying until 8 pm. Whitehurst stated that his supervisors got him all the equipment he asked for, building a “state of the art laboratory.” Although the FBI crime laboratory’s public image was of a cutting-edge forensic unit, Whitehurst found a laboratory with old equipment, rusty gear, and unqualified examiners. Worse yet was the political interference that resulted in laboratory results being altered or changed.

Whitehurst’s training agent made a specifically disturbing statement: he advised Whitehurst, “Before you embarrass the FBI in a court of law, you will commit perjury, we all do it.” In 1989, Whitehurst was working in Explosive Analysis at the FBI crime laboratory and was brought in on an international trial in San Francisco. When he realized a fellow agent was testifying untruthfully, he notified the court officials. He then flew home to talk to his laboratory director in Washington, D.C. Whitehurst was given a verbal reprimand for talking outside of the FBI about FBI business and was given time off. Whitehurst could not understand why senior management at the FBI did not want to hear about false testimony by an Agent in the crime lab. Whitehurst even called FBI Director William Sessions and spent an hour telling him that the crime lab was filthy, an agent was perjuring himself, no validations or protocols were in place, and things were generally out of control in the lab. In 1992, Whitehurst wrote a detailed letter to Senator Joe Biden’s office, noting what was occurring in the FBI crime laboratory. Whitehurst stated that no one seemed to be too concerned about issues plaguing the FBI Laboratory.

Whitehurst was so concerned about perjury by other agents, the state of the FBI crime laboratory, and the complacency of FBI superiors that he started attending law school at night. Four years later, he got a law degree. He was not going to allow a cover-up by senior officials at the FBI. He started writing letters, a total of two hundred and thirty-seven, to anyone he thought would take the issues seriously. The FBI responded by sending Whitehurst on a Fitness for Duty exam (a retaliatory move often taken by the FBI against their whistleblowers). Whitehurst then engaged Stephen Kohn and David Colapinto of Kohn, Kohn and Colapinto, a leading whistleblower law firm in Washington, D.C., to represent him. “I must be stupid to think the truth is important when everyone around me does not,” Whitehurst commented.

Later, Whitehurst was placed in charge of the World Trade Center Bombing laboratory work, but upper management in the FBI was scheming to get rid of him behind the scenes. Whitehurst stated that laboratory reports were changed to “help the prosecutor prove guilt. The lab people thought it was their job to prove guilt.” In 1993, Whitehurst found that his reports were being rewritten and rephrased. One particular case involved a high-profile bombing that senior political figures wanted to place on Iraq’s doorstep. It was Whitehurst’s case, and his reports had been altered to reflect an inaccurate account. Whitehurst questioned, “Why can’t people just tell the truth?”

Whitehurst knew that people with undergraduate degrees in history, political science, and other liberal arts were paid chemists’ salaries and were running tests that chemists should have been running. With a high salary and a large pension, Whitehurst said laboratory technicians were unwilling to tell the truth on cases and rock the boat because they had families, mortgages, and bills. Not only were lab examiners fabricating testimony, but there were testimonial errors, substandard analytical work, and poor practices at the FBI crime laboratory’s chemistry, toxicology, explosives, and material analysis units.

Whitehurst was personally involved in the following investigations: World Trade Center Bombing (1993), Oklahoma City Bombing, O.J. Simpson, Pan Am 103, Y2K Bomber, the assassination attempt against President George Bush, the Boston Marathon Case, the Shoe Bomber case, and the Investigation of the FBI crime laboratory by the U.S. Senate and U.S. Congressional Committees. A memo was circulated inside the FBI captioned the “Whitehurst problem,” which revealed the problem Whitehurst would present for the FBI in the media and with Congress. Director Louis Freeh commented to the media that there was no problem with the FBI crime laboratory, in direct contradiction with Whitehurst.

In 1997, the FBI put Whitehurst on administrative leave. The FBI took Whitehurst’s badge and gun, and he notified his lawyers. Over the next year, the FBI conducted a criminal investigation of Whitehurst codenamed “LabLeak.” The pristine image of a cutting-edge forensic laboratory was crumbling, but instead of investigating the FBI crime laboratory, the FBI’s upper echelon turned their guns on Whitehurst. Starting from his arrival at the FBI crime laboratory in 1986 and until 1997, Whitehurst tried to bring the Laboratory up to standards consistent with the reputation the FBI had put forth for decades. He was the first successful FBI whistleblower and was forced to defend himself and his wife against the FBI’s brutal retaliation.

After weathering a fraudulent Fitness for Duty Exam, the FBI began a series of attacks on Whitehurst. He was placed in a closet for a work environment. They instituted electronic surveillance (his concern was the FBI would patch a false video together) and put him on administrative leave. Cheryl Whitehurst, Fred’s wife, who also worked at the FBI, was harassed and assaulted by a Special Agent while working, forced to suffer for the truth her husband told. Cheryl Whitehurst was constructively discharged (forced to quit) in 1998.

While on administrative leave, Frederic Whitehurst returned to FBI headquarters one day in September 1998. FBI personnel walked him out of the building, a sham parade that the FBI provides their Special Agent whistleblowers. Whitehurst was forced to retire soon afterward and lost his health benefits because the FBI law unit slipped the term “resigned” instead of “retired” into his retirement papers.

During the time of his removal from the FBI, Fred and Cheryl Whitehurst adopted a child. When the child was four years old, she started to internalize the stress inflicted on her mother and father. She was taken to a child psychologist, and in a session, told him, “My mom and dad are sad. Sometimes I am sad too, but I can’t tell them because it will make them more sad.” Whitehurst’s child and wife have suffered lasting trauma, as has he. Whistleblowing affects more than just the whistleblower.

Even though 26 to 28 FBI crime lab examiners lied under oath during the time Whitehurst worked at the FBI crime laboratory, none have suffered any repercussions except for the whistleblower. Asked if Whitehurst would do it again, he replied, “I have to do it again.” Due to Whitehurst’s whistleblowing, the Department of Justice Inspector General (DOJ IG) investigated the lab, and after an 18-month investigation, issued a report.

On April 15, 1997, while Whitehurst was on administrative leave, the FBI received the DOJIG report and adopted 40 significant recommendations to “improve Laboratory policies and procedures and has independently made other substantial improvements in the Laboratory.” The FBI also noted that “the Laboratory needed more and better-credentialed scientists.” The FBI used Whitehurst’s initiatives and complaints (independent accreditation of the Laboratory, more scientific expertise, etc.) as proposals that appeared to have originated from the FBI instead of Whitehurst. In a startling turn of events, the FBI used the problems Whitehurst had identified to press Congress to allocate additional funds to establish a new FBI crime laboratory at the FBI’s Training Academy in Quantico, Virginia. A fitting honor would have been to name the new facility after Frederic Whitehurst, but no FBI whistleblower has ever been honored to this day.

When asked what advice Whitehurst would give a whistleblower, he responded with these questions: “1. Are you married? 2. Do you have children? 3. Can you develop a way to handle stress? 4. Are you prepared to lose your case?”

Whitehurst has been instrumental in the mentoring process of whistleblowers. He serves as the Executive Director of the Forensic Justice Project, and he sits on the Board of The National Whistleblower Center.

David K. Colapinto of Kohn, Kohn & Colapinto LLP is a nationally-recognized advocate for whistleblowers who represented Dr. Whitehurst in tandem with Stephen Kohn. “Fred Whitehurst was a trailblazer,” Colapinto said. “He was the first public FBI whistleblower to have the moral courage to step forward and report violations of law up the chain at the FBI, then to the Attorney General, then to the Department of Justice Inspector General, then to Congress, and then to the United States President.”

Colapinto explained that Congress passed 5 U.S. Code § 2303 in 1989, which prohibited personnel practices in the Federal Bureau of Investigation. Although passed in 1989, the law was not recognized or utilized until Kohn, Kohn and Colapinto found it and applied it to Whitehurst’s case. The statute noted:

(b) The Attorney General shall prescribe regulations to ensure that such a personnel action shall not be taken against an employee of the Bureau as a reprisal for any disclosure of information described in subsection (a) of this section. (c) The President shall provide for the enforcement of this section in a manner consistent with applicable provisions of sections 1214 and 1221 of this title.

Fred Whitehurst’s attorneys took a law that had not been used before and sued the United States President, William Jefferson Clinton, to enforce the law. The President issued an order for the Attorney General to implement the law. It was an act of historical importance and opened up the portal for all federal whistleblowers.

Whitehurst carries wounds from Vietnam and the United States Government. He says he is just a “patriot and American citizen doing his duty,” but he is more than that; he is a hero, a mentor, and an FBI whistleblower extraordinaire.