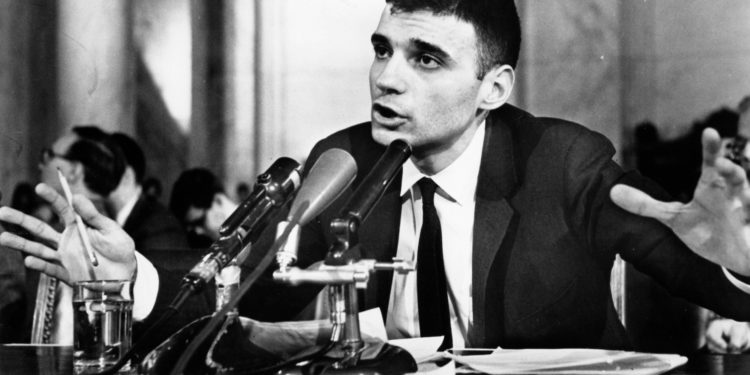

Fifty years ago Ralph Nader sparked the whistleblower revolution by hosting the Conference on Professional Responsibility in Washington, DC. Notice that the word “whistleblower” does not appear in the title. Nader believed employees who report crime and corruption were only doing their job: “the basic status of a citizen in a democracy,” Nader said at the event, includes fulfilling their “professional individual and responsibility.”

During his keynote speech at the Mayflower Hotel on Jan. 30, 1971, Nader presciently observed that employees’ allegiance to society should outweigh that to a company, citizens’ privacy was being eroded by over-reaching organizations, and whistleblower protection laws needed to be passed – including to shield public whistleblowers.

A half-century after what he calls “decisively” the first whistleblower conference ever held in the U.S., Nader says he’s both gratified and surprised by the progress that’s been made since.

“It was one of the more pretentious and effective conferences ever held in the pursuit of democracy. That was the conference that started the whole whistleblowing movement,” Nader said in an interview with Whistleblower Network News. “The people who came to the Mayflower were amazed that anybody could put whistleblowers from government, the Department of Defense, labor unions, corporations, universities all in one room. It was an unheard of dream.”

“You can’t believe how the image of whistleblowers has changed since then – to be bold, courageous defenders of public health and safety, technologies, probity and so on. It’s tremendously gratifying,” Nader said from his office at the Center for Study of Responsive Law in Washington.

“When I started out on the whistleblowing issue, whistleblowers were considered, as you know from history, snitches and disgruntled employees. I wanted to redefine the public understanding of the crucial role of people who take their conscience to work. People who take their conscience to work and practice it are ipso facto professionals.”

This effort to recast witnesses in the workplace as heroes rather than traitors is succeeding, Nader said. “The important thing is how people react when they hear the word ‘whistleblower.’ Now it’s very positive. There is so much publicity now. People identify when a whistleblower at a big company blows the whistle on something. There are thousands of workers who know the same condition, and they bond with this person.”

“I am somewhat surprised [by the progress]. One of the reasons is that I never thought conservatives would support whistleblowing. They support it because of government waste and fraud. That’s really what has strengthened whistleblowing. Whistleblower laws are the subject of repeal efforts constantly. [Opponents] rear their heads once in a while, but they don’t get anywhere. You also have law firms that specialize in whistleblowing, and they are getting more numerous. Even some former authoritarian countries have whistleblower laws. So it does look good.”

Because very high risks of workplace retaliation remain, Nader says he supports granting monetary rewards. “Often the whistleblower loses his or her job. They are subject to calumny, even by their own fellow workers who bond with the employer, and they are blacklisted. They’re asked, ‘Where was your last job? Do you have a recommendation from your last employer?’ So economic rewards in effect neutralize those deprivations.”

By its very nature unstructured and spontaneous, Nader says whistleblowing has a life of its own that cannot be easily suppressed.

“The ethical whistleblowing movement is tremendously decentralized and it can’t be repealed. You can always overturn a court decision, repeal a regulatory action, or elect rascals to replace good legislators. But how are you going to control whistleblowing? By definition it is self-initiating. Because it’s so attached to moral courage, it’s uncontrollable. Moral courage is not tempted by dreams of promotion, ambition, economic reward. It transcends it. It is supreme. And in that sense, because of that conference and what resulted in the U.S. and all over the world, it was possibly the most single important non-governmental conference that generated democratic initiatives and the conscience of the population in American history.”

Whistleblowing mirrors Nader’s fundamental philosophy and strategy of citizen-driven, coalition-based campaigns he’s been leading since he wrote Unsafe at Any Speed in 1965 at the age of 31.

“You see, I’ve always felt that numbers count in justice movements. You can’t just have leaders or a few people. You’ve got to have mass numbers, because injustice works 24-7. Justice needs large numbers that aren’t on your Rolodex: surprising numbers, serendipitous numbers. People who take their religious or social conscience seriously, and don’t reserve it for Sundays or for slogans, are among the finest people you’ll ever meet. They’re being treated better and better.”

While he expects the whistleblower movement to continue to grow in size and influence, Nader said this will not come without a countervailing response.

“There is going to be a pushback as it gets more successful. It’s going to touch some very powerful people and interests. However, it’s sort of a race between further entrenching whistleblower remedies, rights and laws, and the public perception of how valuable whistleblowers are toward making bureaucracies and corporations more accountable. It’s like a see-saw. The more effective it is, it’s going to get a pushback.”

A New Ethic of Whistleblowing: Nader’s Keynote Speech

Here is an except from Nader’s keynote speech from the 1971 conference, from Whistle Blowing: The Report on the Conference on Professional Responsibility:*

“Corporate employees are among the first to know about industrial dumping of mercury or fluoride sludge into waterways, defectively designed automobiles, or undisclosed adverse effects of prescription drugs and pesticides. They are the first to grasp the technical capabilities to prevent product or pollution hazards. But they are very often the last to speak out, much less to refuse to be recruited for acts of corporate or government negligence or predation.

“The key question is, at what point should an employee decide that allegiance to society (e.g., the public safety) must supersede allegiance to the organization’s policies (e.g., the corporate profit), and then act on that resolve by informing outsiders or legal authorities? It is a question that involves basic issues of individual freedom, concentration of power, and information flow to the public.

“Indeed, the basic status of a citizen in a democracy underscores the themes implicit in a form of professional and individual responsibility, and places the responsibility to society over that to an illegal, negligent or unjust policy or activity.

“The willingness of and ability of insiders to blow the whistle is the last line of defense to ordinary citizens have against the denial of their rights and the destruction of their interests by secretive and powerful institutions. As organizations penetrate deeper and deeper into the lives of people – from pollution to poverty to income erosion to privacy invasion – more of their rights and interests are adversely affected.

“There is a great need to develop an ethic of whistle blowing which can be practically applied in many contexts, especially within corporate and government bureaucracies. For this to occur, people must be permitted to cultivate their own form of allegiance to their fellow citizens and exercise it without having their professional careers or employment opportunities destroyed.

“This new ethic will develop if employees have the right to due process within their organisations and if they have at least some of the rights – such as the right to speak freely – that protect them from state power.

“The whistle blowing ethic is not new; it simply has to begin flowering responsibly in new fields where its harvests will benefit people as citizens and consumers. However, the exercise of ethical whistle blowing requires a broader enabling environment for it to be effective.

“The law must be changed to make protection of the responsible whistle blower possible. They should have the right to “go public,” and the corporation should expect them to do so when internal channels of communication are exhausted and the problem remains uncorrected.

“Organizational power must be insecure to some degree if it is to be more responsible. A greater freedom of individual conviction within the organization can provide the needed deterrent – the creative insecurity which generates a more suitable climate of responsiveness to the public interest and public rights.”

*Whistle Blowing: The Report on the Conference on Professional Responsibility, edited by Ralph Nader, Peter Petkas and Kate Blackwell. (New York, NY: Viking Compass/Grossman Publishers, 1972.)