How long does it take to fight the good fight? How long can one stand in the arena and continue the battle? For some whistleblowers, it can be decades, and William Sanjour is a case in point. For half his life, he has been a whistleblower and a whistleblower advocate. He was the point man in a court case that reverberates to this day, and he outsmarted many people who tried desperately to silence him.

Sanjour was born in the Bronx, New York City, and is currently in his late eighties. His father was a carpenter, and his mother died when he was a child. Sanjour’s ancestors and relatives had proven time and time again that they did not back down in a fight when their cause was righteous, and Sanjour wears that personality trait like a suit of armor. His father came from Russia and was a “wobbly,” a member of the Industrial Workers of the World, described as “revolutionary industrial unionism.” Sanjour was also blessed with a high I.Q. He went to several public schools and attended college at City College, New York. He graduated from Columbia University with a master’s degree in physics in 1960.

Sanjour started his career as an operations research analyst with the Navy, and then “bounced around with several jobs” until a manager consultant job became available at Ernst & Ernst, an accounting company. While at Ernst & Ernst, Sanjour had a client affiliated with the government agency handling air pollution. Sanjour conducted studies for the client in the late ’60s before the founding of the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). The EPA was established in 1970, and Sanjour joined in 1972. In 1974, Sanjour was appointed to EPA branch chief and was highly successful in hazardous waste damages and treatment technologies.

In 1978, the Carter Administration removed the hazardous waste regulatory effort’s penalties to assist the economy by helping manufacturing industries. Sanjour felt the administration orders “were illegal and inconsistent with the congressional mandate to ‘protect human health and the environment.’” Sanjour kept a record documenting what was happening regarding hazardous waste, but the documents disappeared. Due to his whistleblowing, Sanjour was then transferred to a position with “no duties and no staff.” Even though he was marginalized and retaliated against, Sanjour continued to speak out against the lax EPA hazardous waste policy.

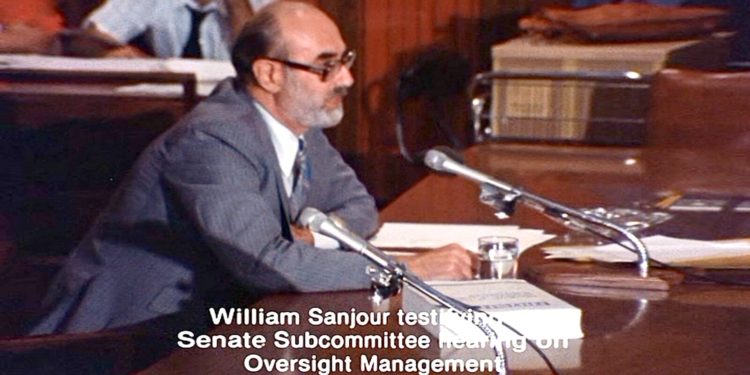

Sanjour continued writing memos documenting orders to relax hazardous waste regulations, his superior’s cover-up of the charges, and the EPA’s exclusion of key industries from dangerous waste regulations. The EPA continually removed Sanjour’s memos until Sanjour was invited to testify before the Government Management subcommittee. Sanjour felt that the “hearing was a benchmark in my life. It showed me that whistleblowing could work if done intelligently.” Sanjour was reinstated to the Hazardous Waste Management Division and never stopped his whistleblowing. His studies of hazardous waste damages and treatment led to the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act of 1976 (RCRA).

Over his thirty-year career as an EPA policy analyst, Sanjour repeatedly blew the whistle on EPA actions that endangered public health or the environment. He “became the conduit for others in the government-industry and environmentalists, who had information about EPA waste fraud and abuse.” He would “investigate these charges, and if I felt they had merit, I would bring them to the attention of the administration or the inspector general, making sure that copies went to Congress and the press.” Sanjour fought to make the RCRA a useful tool in developing regulations for the treatment, storage, and disposal of hazardous waste. Still, he suffered retaliation, reassignments, and demotions as he had to blow the whistle several times to have the EPA follow the regulations.

Sanjour said he “became a whistleblower because my attitude has always been that the public has paid for the information that I had acquired on my job and that the public is entitled to what it paid for. Just as it is wrong for employees of a corporation to withhold information about how the corporation’s management was lying, cheating, or stealing from the stockholders, it is wrong for government employees to withhold such information about the government from the public, who are, in essence, the United States’ stockholders. Indeed, federal law requires federal employees to report government waste fraud and abuse. Sadly, so few have the courage to do so, and so many have the ambition to avoid doing so. Whistleblowers should be protected, encouraged, and rewarded. They are the most effective and inexpensive enforcement personnel.”

Throughout his career, Sanjour overcame many obstacles to blow the whistle effectively. Although, Sanjour admits that whistleblowing is “in his genes,” he is also aware that whistleblowing is not for everyone. Over his whistleblowing career, Sanjour was involved in many high-profile environmental cases, always making sure his memos concerning EPA negligence, waste, fraud, and abuse would go to his superiors, the inspector general, Congress or the press.

Lois Gibbs was the critical leader of Love Canal, NY residents in their 1978 fight to be relocated away from a toxic dump containing over 20,000 tons of chemicals. Gibbs asked Sanjour to be a technical advisor for her organization, the Center for Health Environment and Justice, which grew out of the Love Canal struggle. Sanjour accepted the offer and started flying around the country on his own time, helping environmental groups. Sanjour stated that his decision to be a technical advisor “changed him from being a one-time whistleblower to an almost permanent one.”

Before 1991, federal employees could accept travel expenses from anyone except prohibited sources. In January of 1991, the federal Office of Government Ethics published an interim rule in the Federal Register. It noted that “An employee (federal government) is prohibited …from receiving…[travel expenses for speaking…on subject matter that focuses specifically on the responsibilities, policies, and programs of his employing agency.” Sanjour felt that after years of frustration at the EPA over his whistleblowing and travels to speak at environmental events, the EPA had a law written to curtail Sanjour’s trips. With the Office of Government Ethics’ collaboration, the EPA issued regulations to prevent Sanjour from receiving travel expenses when addressing an audience on his own time. Sanjour frequently traveled and gave speeches, in an unofficial capacity, often criticizing EPA policies. He depended on travel expense reimbursements from private sources to reduce his cost of speaking engagements.

After canceling speaking engagements, Sanjour turned to Stephen Kohn at the National Whistleblower Center for help. Kohn thought the new law was unconstitutional and offered his law firm Kohn, Kohn and Colapinto to assist Sanjour pro bono. Kohn wrote to the EPA and stated, “There is no regulatory basis to prohibit Mr. Sanjour from accepting travel reimbursement. But even if there were, such restrictions would violate Mr. Sanjour’s right to freedom of speech under the U.S. Constitution. Requiring an employee to pay out of his pocket, and not accept travel reimbursement for out-of-town speaking engagements would severely impede Mr. Sanjour’s right to speak out on matters of public concern.” Kohn continued, “Not only would such a regulation be unconstitutional on its face, but it would be retaliatory as implemented against Mr. Sanjour. Mr. Sanjour has, in the past, criticized the conduct of the EPA in out-of-town speaking engagements.” Kohn felt that “establishing a regulation which impeded such conduct would be retaliatory and would violate Mr. Sanjour’s (and the public’s) First Amendment rights.”

Kohn and Sanjour battled the EPA for four years, and on May 30, 1995, in a case that impacted every government employee, the United States Court of Appeals, District of Columbia Circuit, in William Sanjour et al., Appellants, v. Environmental Protection Agency, et al., Appellees, found “that the government has failed to demonstrate that the interests of the employees and their potential audiences in the speech suppressed ‘are outweighed by those expressions necessary impact on the actual operation of the government.’” The Court also noted, “It is perhaps the most fundamental principle of First Amendment jurisprudence that the government may not regulate speech on the ground that it expresses a dissenting viewpoint.” The Court went on to rebuke the government by adding, “It, therefore, appears that employees may receive private reimbursement for travel costs necessary to disseminate their views only by toeing the agency line.” The Court concluded: “Government employee speech is protected by the First Amendment, and can only be infringed when the government demonstrates that the burden on such speech is ‘outweighed by (its) necessary impact on the actual operation of the government’……The regulations challenged here throttle a great deal of speech in the name of curbing government employees’ improper enrichment from their public office. Upon careful review, however, we do not think that the government has carried its burden to demonstrate that the regulations advance that interest in a manner justifying the significant burden imposed on First Amendment rights.”

Sanjour not only protected the public from toxic waste, but he was also responsible for a landmark case which resulted in expanded whistleblower protections. “Most whistleblowers,” said Sanjour, “do not start to blow the whistle on anyone. They do what they think they ought to be doing. It is important to remember that one becomes a whistleblower not because he thinks of himself as such, but because others view him as a whistleblower.”

When asked what advice he would give a whistleblower, Sanjour stated, “My advice to people in general, is don’t be a whistleblower. Avoid open challenge or defiance of authority or power. Try to satisfy your conscience or your sense of duty without getting personally involved. For example, you can leak stuff to a known whistleblower who is willing to take the heat, or to an activist organization, or a plaintiff’s attorney. I would advise a prospective whistleblower to know the law, the rules, and one’s rights long before you start. Know what to expect by talking to people who have been down the road. Read books and articles about whistleblowers and whistleblower protection laws. Small, subtle differences in how you blow the whistle, what you blow it on and where you blow it can make significant differences in the kind of legal protection you have. If legal counsel is needed, get the name of an attorney who specializes in whistleblowing. Do not rely on local attorneys. They are probably not familiar with the laws protecting whistleblowers, and they are often subject to local pressures which may be against your interests.”

Sanjour continued, “Keep good contemporaneous records, i.e., meeting notes, phone logs, calendar, diary, etc. These carry a lot of weight in legal proceedings, much more so than accounts written months after the fact. However, if you elect to become a hard-core whistleblower, then elect it, don’t stumble into it. Please don’t count on having your cake and eating it. Don’t think you can continue defying the-powers-that-be and still enjoy the same lifestyle as before just because you are right or acting within your profession’s confines. Many whistleblowers have been destroyed by that kind of naïveté (or professional arrogance).”

Sanjour retired from the EPA in 2001, after decades of blowing the whistle in that agency. He received the Association of Certified Fraud Examiners Cliff Robertson Sentinel Award in 2007, which is bestowed on a person who, “without regard to personal or professional consequences, has publicly disclosed wrongdoing in business or government-the unselfish hero whom society has tarred as being a whistleblower.”

Sanjour considers Martin Luther to be the perfect model of the “professional turned hard-core whistleblower.” Luther was an ordained priest and doctor of theology, and he raised specific moral and theological issues for debate. This was perceived as a challenge to the church, who proceeded to harass Luther. Luther spoke the words Sanjour believes can serve as the official credo of whistleblowers, “Here I stand. I cannot do otherwise.”

Read more:

Introductory Remarks for Undeclared Whistleblowers by William Sanjour, September 18, 1993.