The growing campaign to strengthen protections for whistleblowers who expose climate threats aims to provide a safety net of defense from retaliation for future generations of citizens.

These protections come decades too late for people like Steven Donziger.

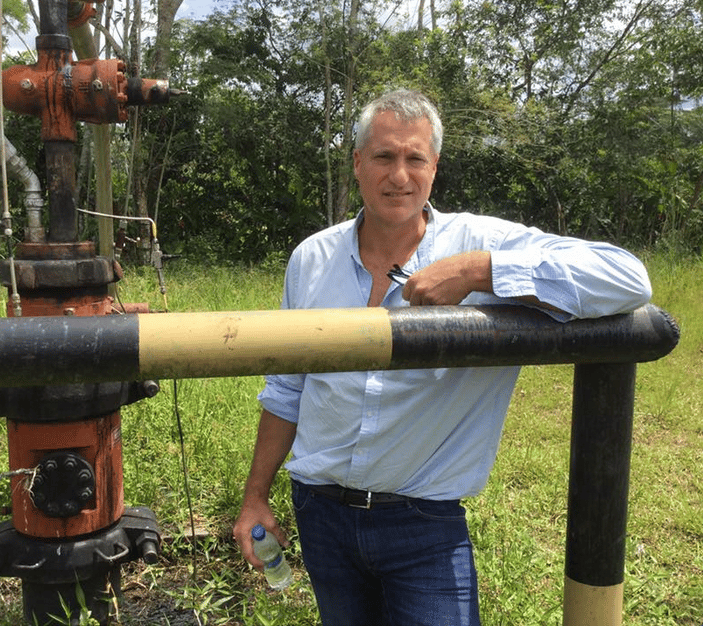

He may not be a whistleblower in the most literal sense, but in 1993 Donziger and other attorneys in New York sued on behalf of more than 30,000 Ecuadorian indigenous residents who claimed drilling by Chevron had polluted their rainforest home and sickened local community members. In doing so, Donziger exposed Chevron’s criminal environmental wrongdoing to the world.

A judge in Ecuador returned a multibillion-dollar judgment against Chevron in 2011, doubling the punitive damages to $19 billion after Chevron refused a court order to apologize. The company’s response since then has been twofold: avoid paying and ruin Donziger’s life. They have succeeded on both counts.

“Our [long-term] strategy is to demonize Donziger,” Chevron wrote in an internal memo in 2009. Two years later Chevron filed a racketeering (RICO) suit against Donziger in the US, accusing him of judicial bribery, writing the judgment against the company, and faking scientific studies.

US District Judge Lewis Kaplan ruled in 2014 that Donziger’s conduct was “criminal,” affirming most of Chevron’s allegations against him. In a rarely used judicial maneuver, Kaplan appointed a private law firm with ties to Chevron to prosecute Donziger after the US Attorney’s Office in the Southern District of New York declined taking the case.

Kaplan found Donziger had conspired to fabricate evidence and blocked Donziger from collecting more than $550 million in legal fees. As a result of this ruling, Donziger was disbarred and is no longer allowed to practice law. He has been on house arrest on appeal since 2019, and was convicted this past July by US District Judge Loretta Preska on six counts of criminal contempt of court for refusing to turn over his cell phone and confidential documents to Chevron.

On September 24 the UN Human Rights Council ruled judges with a “conflict of interest” engaged in a “staggering display of lack of objectivity and impartiality” in Dongizer’s case. The Council found his lengthy home confinement was “arbitrary” which resulted in Donziger’s “deprivation of liberty” under the UN’s Universal Declaration of Human Rights guidelines.

Council members added a strong editorial: “The Working Group is appalled by uncontested allegations in this case.” The next day, September 25, Judge Preska imposed a six-month sentence on Donziger.

Earlier this year, six members of the Congressional Progressive Caucus co-signed a letter to the US Department of Justice demanding review of Donziger’s case.

For every high-profile case like Donziger’s, untold numbers go unreported. In the early 1990s at my first journalism job, I received a phone call from a gentleman who said he worked at a munitions manufacturing facility in North Carolina that had been designated as a federal Superfund site.

He told me one of his jobs was to pour hazardous waste into an open pit and set it on fire. What they couldn’t burn, he said, they dumped untreated into the river. What didn’t get dumped in the river was buried in hundreds of 55-gallon drums along the riverbank. He said he had called to tell me exactly where the pits had been dug and the barrels were buried, in hopes that these areas would be included in the site’s cleanup plans. He wouldn’t give me his name because he feared losing his retirement benefits if the company found out he was the source of the information leak.

This man’s voice held a noticeable tremor as he spoke, and I asked if he was nervous speaking with me. He said he suffered permanent neurological damage, cognitive difficulties and debilitating pain caused by exposure to the chemicals. Yet his biggest pain came from regret over his actions of decades before, and his conscience had finally compelled him to blow the whistle on his employer of 20 years. Had a strong whistleblower protection law been in place, he might have been able to report the malfeasance sooner, without fear of retaliation.

We cannot go back in time and undo this damage, but going forward we are working to ensure that climate whistleblowers are afforded the legal protection they need to safely report these corporate crimes before they become the toxic-waste sites of the future.

One tool we can use in climate defense is the enactment of laws with strong enforcement regulations that protect climate whistleblowers from harassment, with clear legal mechanisms that enable the justice system to enforce whistleblower laws. Legislative language should include the word “climate,” to ensure climate whistleblowers are afforded full protections under the law. Climate whistleblowers should know where to report company wrongdoing, who will be responsible for investigating their claim, where to turn if they are fired in retaliation, and what the outcome of their reporting will be.

Climate whistleblowers must be protected. They deserve every encouragement, backed by full legal support, not employer retribution. Climate is the terminology of the future, and the future is now.