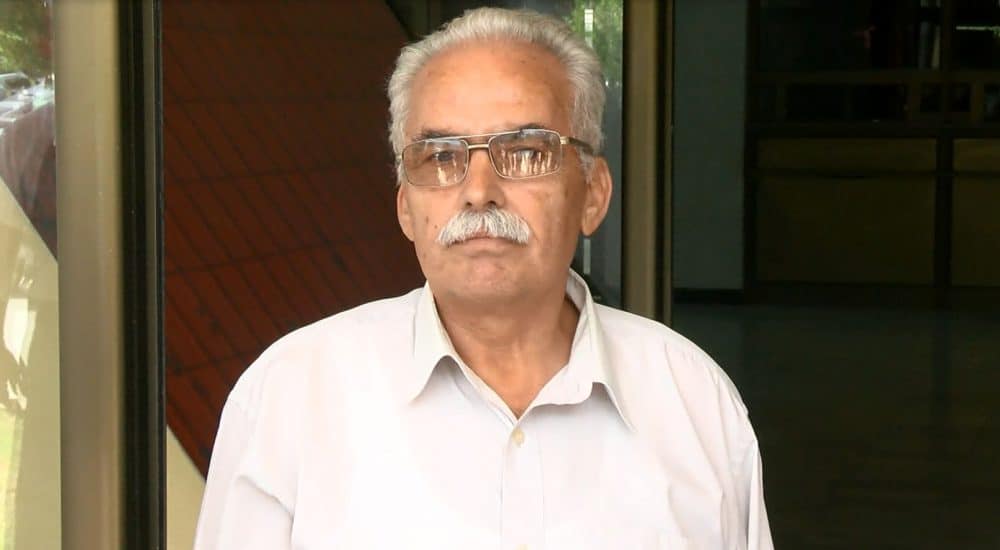

Nearly three years after local media declared him an “overnight public hero and role model,” Gjorgji Ilievski finally has obtained justice. An appeals court in Skopje has ruled that officials are required to investigate the corruption allegations raised by the former North Macedonian education inspector.

North Macedonia passed one of Eastern Europe’s first whistleblower protection laws in 2015, which on paper contains many best practices. It was widely praised as a groundbreaking measure to curb corruption in the fragile Balkan country infamous for its political cronyism.

When it came time to investigate Ilievski’s case and protect him from retaliation, however, the law was absent – along with the public officials responsible for enforcing it.

Ilievski was serving as a chief inspector for Macedonia’s Education Ministry in April 2019 when he learned that three well-connected politicians – including the education minister himself – had improperly obtained professorships and other academic titles at the State University of Tetovo.

Ilievski told many public authorities about the irregularities, including his supervisor, prosecutors, the financial police and the State Commission for Prevention of Corruption (SCPC). Ilievski said he was pressured to stay quiet and withdraw his reports, and he was cautioned because he has a family and children, the Southeast Europe Coalition on Whistleblower Protection reported.

Ilievski was transferred, threatened with demotion and no longer given any work assignments. Meanwhile, one of the politicians he accused of misconduct is now a member of Parliament, and another is a deputy justice minister.

The SCPC, which has the primary duty to investigate corruption and protect whistleblowers, did neither. The agency said it was not required to investigate the three politicians’ alleged misconduct. And it said Ilievski was not entitled to whistleblower protection due to an obscure bureaucratic technicality – namely, not filling out the proper paperwork.

This past Dec. 15, a Higher Administrative Court overturned a lower court’s decision and ruled that the SCPC’s decision not to investigate the case was incorrect. The court did not rule on Ilievski’s whistleblower status since he did not formally request protection.

Ilievski celebrated the victory in a lengthy letter to the Macedonian public. “I am proud because you readers gave me full support to endure. You wrote a petition with more than 5,000 signatures under the heading, ‘Stop Crime and Corruption.’ Journalists gave me unforgettable and strong support.”

“Their goal was to break me, but my strength and spirit could not be broken,” Ilievski wrote. “I succeeded therefore I am proud, and will I continue to discover all educational crimes.”

Now retired with a full pension, Ilievski has written the book, “The Rot of the System in Macedonia,” and he is planning a second. “Many people in Macedonia have high-ranking positions without having proper diplomas, or even with false diplomas,” he told WNN via a translator. “I do not plan to give up my fight for better quality education.”

“We have an institutional crisis and a normative crisis. In connection with all of this comes corruption and crime,” Ilievski said in a nationally televised interview on Jan. 21. “The crisis is that all of our institutions are partisan.”