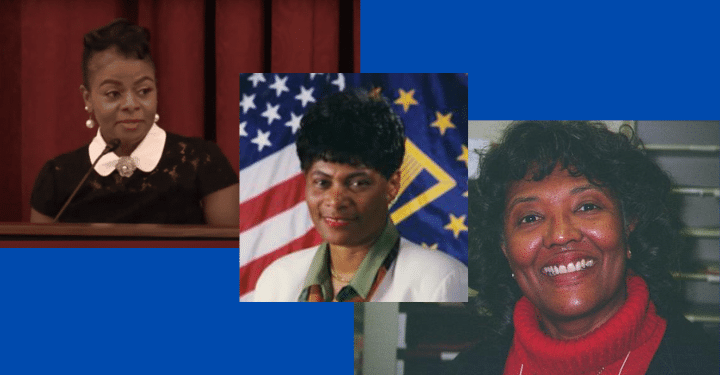

As Black History Month transitions into Women’s History Month, WNN highlights Dr. Toni Savage, Bunny Greenhouse, and Dr. Duane Bonds, whose outspoken whistleblowing activity against corruption led to significant change.

Michael D. Kohn, founding partner of Kohn, Kohn, & Colapinto and the attorney who represented these whistleblowers, says they are “American heroes” and that “[their] courage led to sweeping legal reforms that will forever halt the gross abuse [they] dared to expose.”

Dr. Toni Savage

Dr. Tommie (“Toni”) Savage’s federal employee whistleblower case has stretched on for nearly a decade and a half since she began to experience retaliation for blowing the whistle on systemic contracting fraud within the Army Corps of Engineers. Her case before the Merit Systems Protection Board (MSPB) established the right for federal whistleblowers to pursue hostile work environment claims.

Dr. Savage became a whistleblower shortly after being named to head the Army Corps of Engineers’ Huntsville, Alabama contracting office. Savage found rampant government contracting fraud and raised concerns internally to the highest levels of the command, but nothing was done. She then went to the auditing department. The auditing department confirmed all her allegations of contract fraud. Subsequently, they were all corroborated by two high-level Army AR 15-6 investigations.

Dr. Savage alleged that her whistleblowing caused her workplace to turn hostile. She complained of numerous retaliatory actions (demotion, downgraded performance reviews, failure to issue awards, failure to issue interim evaluations, unrealistic deadlines, and refusal to staff her office, resulting in an overwhelming and unmanageable workload. She was also subjected to racially insensitive remarks). Eventually, Dr. Savage began to suffer debilitating panic attacks when she entered the workplace. She was charged with AWOL (absent without official leave) and permanently removed from federal service when she could no longer return to her work environment.

After years of litigation, a landmark decision emerged when the Board adopted Dr. Savage’s argument that the protections under the Whistleblower Protection Act extend to hostile work environment claims. Federal whistleblowers can now raise a hostile work environment claim in defense of a removal action.

In 2017, Dr. Savage spoke on her experience blowing the whistle as a keynote speaker at National Whistleblower Day.

Recently, Dr. Savage filed a new complaint regarding the government’s lack of performance under an agreement to pay damages to and issue a formal letter of gratitude for her government service and thanking her for her outstanding performance.

Bunnatine “Bunny” Greenhouse

Bunnatine “Bunny” Greenhouse was the first African American woman to hold a Senior Executive Service position within the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. She was the Procurement Executive and Principal Assistant Responsible for Contracting (PARC), the highest-ranking contracting official in the Army Corps of Engineers, at the height of the Iraq war. She discovered and exposed government procurement fraud.

The U.S. Army gave millions of taxpayer dollars to the Halliburton company through no-bid contracts, costing taxpayers millions of dollars in waste, fraud, and abuse. Though every other Army official joined in on this scheme, Ms. Greenhouse was the only one to protest this. She wrote right on the face of one of Halliburton’s contracts and illegally directed contracts to Halliburton subsidiary Kellogg Brown and Root (KBR), which caught the Defense Department officials’ attention. However, the same officials steered the contracts to KBR on subsequent contracts, bypassing her authority. Despite warnings from her supervisors, Ms. Greenhouse spoke out and became a whistleblower.

The Defense Department Inspector General investigated Ms. Greenhouse’s allegations. As a result of her outspokenness and the public attention on this matter, the government revised the contract to what Ms. Greenhouse initially recommended. In 2007, Ms. Greenhouse testified before the Democratic Policy Committee hearing on the protection of whistleblowers.

After her exposure and testimony, she faced countless acts of retaliation in her work. Due to her high-ranking position, she couldn’t be fired. However, she was demoted and stripped of her security clearance. After her whistleblower lawsuit, someone at her workplace set up a tripwire around her cubicle, and she fell. She sustained permanent knee damage.

The whistleblower case was about the retaliation she faced for speaking out and faced discrimination based on race, gender, and age. In 2011, she agreed to a settlement of $970,000 in full restitution of lost wages, compensatory damages, and attorney fees. This six-year legal battle closed this turbulent chapter in Ms. Greenhouse’s life.

Bunnatine “Bunny” Greenhouse put her career on the line to stand up to corruption in the United States Army Corps of Engineers. After almost thirty years with the federal government, Ms. Greenhouse retired soon after her settlement.

In June 2019, Greenhouse was featured in a news documentary on the CBS program Whistleblower, available to watch online.

Dr. Duane Bonds

Dr. Duane Bonds served as Deputy Chief of the Sickle Cell Disease Branch of the Division of Blood Diseases and Resources within the National Institutes of Health in 1999. Despite being a distinguished medical researcher, Dr. Bonds experienced sexual harassment from her supervisor. She reported the issue but was subjected to removal from her position and demoted.

However, in this new position, Dr. Bonds made a discovery. She found that blood from African American infants was taken from participants without consent, which was used to duplicate the cells for future studies. She initially raised these concerns internally, but her supervisor retaliated against her by submitting negative performance reviews. This retaliation led to her removal from the project.

Dr. Bonds reported this unauthorized cloning to the Office of Special Counsel (OSC). The OSC determined that NIH officials had violated federal law. She continuously experienced discrimination and harassment and was ultimately terminated in 2006, shortly after NIH officials illegally searched her computer and found the complaint to the OSC.

Dr. Bonds filed multiple Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) complaints. Her final EEOC complaint was in 2007 before she filed the case with the District Court. In 2011, the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit ruled in favor of Dr. Bonds in Bonds v. Leavitt, 629 F.3d 369, 384 (4th Cir. 2011), declaring that she had a right to a jury trial for her claims under the Whistleblower Protection Act. The case was subsequently settled.

Conclusion

All whistleblowers face immense pushback and adversity in their commitment to break silence and bring light to wrongdoing. But Black women whistleblowers face uniquely challenges as the pervasiveness of racism and sexism extend into whistleblower retaliation.

These three whistleblowers’ resilience is a testament to their commitment to advocating for justice and ensuring accountability is transparent within the government.